< Prelude | 01 | 02 | 03 | 04 | 05 | 06 | 07 | 08 | 09 | 10 | 11 (Special) | Postlude >

- Limit Case

- CATEGORY: Writers’ Room

- CATEGORY: Visual Big Finish

- CATEGORY: Nostalgia

- CATEGORY: Whittaker

- CATEGORY: Faux-woke

![doctor_who_2005.11x05.720p_hdtv_x264-fov.mkv_snapshot_43.55_[2018.11.10_17.31.51]](https://gigawho.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/doctor_who_2005-11x05-720p_hdtv_x264-fov-mkv_snapshot_43-55_2018-11-10_17-31-51.jpg?w=863)

Limit Case

We have reached the halfway mark of Series 11. It’s time to take a leaf from Thirteen’s book and ask a rapid sequence of expository questions. What have we learned? Where are we now? How do I proceed from here?

After each of the four prior episodes, I arrived at an opinion about how Chibnall’s Who works. From The Woman Who Fell To Earth, I judged that the show was making a superficial performance of empathy to mask its deep-seated cynicism. I concluded after The Ghost Monument that it was an episode designed to only be half-watched, frustrating any attempt at visual or narrative analysis. Rosa sent me into a spiral of horror at how the accepted structures of Doctor Who, and undoubtedly Chibnall’s looming co-credit, warped a story of social struggle into shallow comfort food for the privileged. While trying to strain meaning from Arachnids in the UK, I briefly glimpsed a chasm of existential emptiness behind the story’s chaotic ethics.

That last one was a joke, though. I certainly had fun with it, but I was parading a dead horse. It was a showcase of an approach that has obviously become defunct. I may have cited real lines and images from the episode as supporting evidence, yet what could that ever reveal about a televisual event that rejects citation itself? Something that doesn’t even ask to be watched in full, or in order, let alone rewatched? You could sit around for hours and hours coming up with detailed, flowery symbolic readings of any of these episodes, and the most it might achieve is help you to forgive them for existing. That might even be something worth doing in a few years’ time, when the event is behind us and the video artifact is all that remains, but right now? We have to stop fantasising and look at what we really want out of our relationship with Doctor Who.

Because there is a case to be made that all of this is pointless.

There are people on the internet with experience in how to write and create effective stories, applying that knowledge to write detailed breakdowns of why this episode or that episode isn’t as good as it could have been. If you’re reading this you may have already seen one of Andrew Ellard’s Twitter threads, which are good reads. Whenever I read one I experience a creeping dread at the thought that all of it might be a complete waste of time, utterly disconnected from what is happening in the living rooms of Chibnall’s target audience.

For example, I have little doubt that no piece of criticism written by a Doctor Who fan above the age of twelve has ever accurately described how the show is experienced by its youngest viewers. Likewise, does a dressing-down of a Doctor Who episode for not correctly building tension in the first half, or failing to resolve someone’s character arc, or missing opportunities to bring together its themes, mean absolutely anything to anybody who doesn’t generally give a toss about the inner mechanics of a children’s show (or ostentatiously trot out words like “Aristotelian” and “Brechtian”)?

These observations certainly help us articulate why we are unsatisfied with it. But does that make them inherently worthwhile? It’s not as though we matter. It’s not as though this show, of all shows, wants or needs us to continue liking it. Why are we watching it? Why are we talking about it? What the fuck are we doing?

Alienation. Maybe everyone who likes Doctor Who ends up going through this in the end, or maybe it’s just the subsection of fans who like to think about it a lot and treat it like art. Nonetheless, I believe a not-unique experience with Series 11 is that of gradually becoming aware of your disenfranchisement as a spectator. The slow realisation that your form of spectation is no longer invited; that you can do naught else but “watch it wrong“.

I resigned myself to this before the first episode even aired, hell, I was steeling myself since Comic Con (as some embarrassing posts on this blog can attest). True, I still manage to occasionally be surprised at just how bad Series 11 is at appealing to me. At upholding my standards. But I went in knowing I was not the audience, that I would watch it wrong, and here we are five episode posts in anyway.

Trouble is, it’s getting more and more difficult to bother. Writing this right now, I have no idea if I will even finish it before Demons of the Punjab airs. (I might put off watching it till I finish, just for the sake of maintaining the chronology.) Listing all the nitpicks I have every week, returning over and over to the same notes like “Yaz is severely underwritten” or “Chibnall’s dialogue sucks”, it’s like hitting a diamond wall. The longer prose sections are more enjoyable, but I’m clearly running out of new things to say with those as well if Arachnids is any indication. It’s unclear to me whether I’m talking about anything real and meaningful, or just gibbering away to myself in a corner. Not a motivating position to be in.

One possible justification for continuing to write the posts is that disenfranchisement is a sad experience, and one that needs to be processed. But that begs the question, is this really the healthiest way to be going about it? Does this process genuinely make me, or you, happier? Or if not happy, then at least productively angry?

Even if it does, to what end? A lot of people are having fun with Series 11, as we’ve noted – not just that, but a lot of people understandably need it to be good, to the point where there’s a bit of a general reluctance among publicly-visible fans to really lay into it. And is that not right? Isn’t all this moaning and denouncing just a pathetic attempt to ruin the fun?

Wait a minute…

Er…

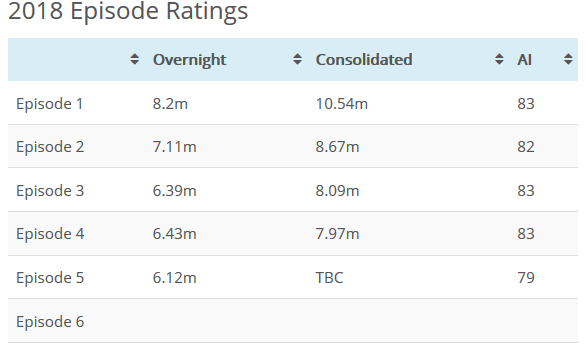

Hang on. This is weird. The lowest ever? I struggle to see how The Tsuranga Conundrum is meaningfully much worse than the other four episodes, and yet not only is the internet upset with it – which, on its own, wouldn’t be especially worth paying attention to – but even the British viewing public have had one of their occasional twitches of irritation, and those two things certainly aren’t predisposed to align (the Appreciation Index was only one point higher for Heaven Sent, whereas that story’s reputation among fans speaks for itself).

To be fair, there are some very bad reasons someone might hate this episode. There’s a pregnant man in it, which has elicited accusations that the show is attempting to indoctrinate viewers by depicting a man doing something men don’t often do. The episode also contains a silly-looking, expressive CGI creature of the variety not seen since Partners in Crime‘s Adipose, which seems to enervate a class of viewer who wants Doctor Who to stay as far away from the realm of the cartoon as possible (perhaps because they have some idea that the show needs to take itself seriously at all times). It’s normal to dislike Doctor Who episodes for all kinds of silly reasons. Remember that time everyone flipped out because the moon was gaining mass and there was a magic dragon inside it?

And yet…RTD not only created the Adipose, he had human characters making hybrid babies with cat people. His era invited this exact type of whinging, and it was still enthusiastically beloved. Sure, ten years have passed, but people have spent that entire period of time grousing that the show was better before Tennant left, so it must retain some of its appeal.

In contrast, Chibnall’s run isn’t exactly on a fixed upward trajectory. It’s trying to tame a fickle beast, and while it might be performing more healthily than the Capaldi years, things are looking mixed. What’s Chib doing wrong (or perhaps, what isn’t he doing right) and why is The Tsuranga Conundrum the point at which a crack starts to show?

Allow me to postulate: it’s because this episode is where Chibnall runs out of juice. Not quite in the conventional sense – this might be his most competent script of S11 where ruthless mechanics and grunt work are concerned, if only because it bothers to resolve all its plot threads and keep up a semblance of juggling a big cast. But I feel it represents an extreme, an outer limit of Chibnall Who, in the extent to which it’s about nothing other than itself.

The Ghost Monument agonisingly broached the most basic idea of a Doctor Who adventure on an alien planet, as if it feared the audience wouldn’t understand it. Tsuranga takes this a step further by spending a great many words elaborating on the bold, unprecedented, innovative concept of a plot on a spaceship…and, furthermore, the idea of an optimistic TV show.

DOCTOR: Too fast to chase and capture, too toxic to touch directly. It’s a bit of a puzzler.

MABLI: It’s going to kill us all, isn’t it?

DOCTOR: Whoa, Mabli! You went there way too quick. I said a puzzler, not a death sentence. I mean, it’s a bit of a challenge, and I can’t quite see the solution yet, but that’s life. Or medicine. Patients present problems, you figure them out and come up with solutions. That’s what this is. A problem to be diagnosed. Medicine to be administered. You’re a medic, I’m the Doctor.

MABLI: A doctor of medicine?

DOCTOR: Well, medicine, science, engineering, candyfloss, Lego, philosophy, music, problems, people, hope. Mostly hope.

MABLI: I’m struggling to see much hope here.

DOCTOR: It doesn’t just offer itself up. You have to use your imagination. Imagine the solution and work to make it a reality. Whole worlds pivot on acts of imagination.

(All transcription from Chakoteya.)

There’s speculation afoot that Tsuranga was a rescue script. Chibnall euphemistically mentioned in DWM that a prior member of the writers’ room, Tim Price, couldn’t be “available” to write the script even though he “created and named the alien”. To be fair, that might be the truth; I can easily see the writers’ room being such a banal environment that they were coming up with things like “Puh-ting!” before coming up with any stories. Regardless, the episode represents Chibnall attempting to fashion a script to fill a void around that cuddly little guy, as a result of one of his hires falling through. This is the sort of situation that exposes a writer. What episode do you write when you have no given story to tell? Chibnall’s answer is to fall back, hard, on the basic stated principles of his run.

This gives rise to Tsuranga‘s fundamental vanity. It’s not enough for the show to be about hope and optimism. It has to trumpet this fact. Oh god, at one point after the plot has resolved, a character even says that what happened was “light in dark times”. In the above quoted dialogue, the Doctor describes herself as a “doctor of hope”. Yoss laments that they’re in a “turbulent world”, though which world he means is unclear. The episode doesn’t end with the Doctor and friends returning to the TARDIS and blasting off for another adventure, it drops out on the far more portentous note of the Doctor in the midst of a prayer circle – complete with an incantation that mentions “hope” and “light” again. (Not to mention the self-important contrasting of Avocado’s birth with Eve’s funeral in that final sequence.) It’s an episode that is intensely concerned with proclaiming its own hopefulness – in a way conspicuously similar to how Chibnall was describing Series 11 before it aired. Marketing itself.

The temptation here is to do what we did for Rosa and Arachnids, and look closely to identify the relative lack of hope actually being offered by the story’s vision of the future – but maybe we shouldn’t fall back into that trap just yet. We’re trying to talk about the show people are watching on Sunday night, not the mangled palimpsest of interpretations we’re still picking over on, uh, the following Sunday afternoon (god I left this late).

We should consider how grating and mawkish this kind of soapboxing from Chibnall might be, even to the lay viewer. The masses are tuning in to see what’s been advertised – a bit of harmless fun, perhaps a bit of drama – not further advertisement, certainly not for awkward gestures at profundity.

Yet this is Chibnall’s core ethos for Doctor Who, standing revealed in its purest form. The Doctor is a “pillar of hope” because she explicitly tells people she is one and that they should have hope. She does this in a story that allots time for her to explain why it’s good that she uses her imagination to solve problems, and to wax lyrical about how cool it is that a spaceship can fly. It starts to look like there’s an absence of specific things to talk about, so the underlying premises get re-explained instead. Like it’s all a bit hollow, no?

Well, that’s only to be expected. Hope and wonder are things that emerge from circumstances. In a vacuum, they evaporate. To fetishise them for their own sake is to relieve them of any substance or meaning.

I may chew Chibnall out a lot for his cynical hackery, but I do believe he himself just wants to create television that makes people’s lives brighter – the issue is, his understanding of how to do that is rather shallow. We’ve noticed that he’s working with warped and half-considered ideas of hope, happiness, catharsis, justice and morality; all of this stems from an unwillingness to seriously consider what the substance of the show is now. “Just make it, really.” It’s not that Chibnall can’t write anything with an idea behind it, or intended to make the viewer think, or with a sense of purpose (the last season of Broadchurch certainly put paid to that one). It’s that he won’t bring this to Doctor Who. And maybe that ties all the way back in to what we were saying after episodes 1 and 2; getting specific risks alienating viewers.

Except of course, as we may now be starting to see the first hints of, treating viewers like idiots also alienates them. Trying to explain fun to them from first principles, instead of letting them have fun, is relatively unproductive. Even more so when you’re trying to walk the thin line of not pissing them off with a cartoon alien or a pregnant male (written in the most inoffensive way possible, btw).

We speak of watching Doctor Who “right”, and “watching it wrong”. But what happens when even watching it right fails? What if, upon some quirk of fortune as simple as Chibnall becoming devoid of ideas, his target audience tires of him and Doctor Who yet again slumps in the public estimation?

I’ll level with you. I don’t want Series 11 to go down in popular culture as the one that ruined the show “because the monster looked silly”, or “because they talked about racism”, or “because they had a pregnant male alien and it was indoctrination”, or indeed “because it was a woman”. None of those things matter to me. But one way or the other they will persist as a strain of criticism, even if Chibnall’s era goes exactly as planned overall. And the unpleasant truth is that they’re all the kind of observation that comes from watching Doctor Who “right”, i.e. not thinking about it, not applying cogent standards to it, not wanting to be challenged by it, not holding your own preconceptions to scrutiny.

If that voice is allowed to be the dominant critique of Chibnall Who, nothing good can come of it: either the show is successful and any objections are dismissed, lumped in with those laughable complaints, or the show is unsuccessful and people casually begin to take those complaints as received wisdom. Either way it spells something bleak for the future of Doctor Who – a lack of constructive growth.

This is why there have to be people who watch Doctor Who wrong. People who expect no less from it than what they know for a fact Doctor Who can give them. This might mean a lot of different things, and not everyone will be on the same track or indeed a useful one. But anyone who likes Doctor Who in any way, and finds that they’re critical of it for even the smallest reason, owes it to both themself and Doctor Who to be honest and open on the matter. You learn things when you criticise or hear someone else’s criticism; you help build up a base of thought and theory that elucidates one tiny, subjective corner of the world. It’s never a truly futile task, at least any more so than thinking or breathing.

There need to be voices saying “because the monster was uninspired”, or “because they promoted an unethical attitude to social progress”, or “because they made the mpreg guy a comedy alien to distance him from the viewer”, or indeed “because the first woman to lead the show was handed a bland version of the character”. If everybody thinking those things just decided to give up, say nothing and forget about the show, how could anything good ever happen to it again?

Even the reverse is true – who will stick up for the times when Doctor Who is rare, exquisite, idiosyncratic, and tragically overlooked by those who are “watching it right”? If Series 11 does something you think is incredible but idiots hate it, will you argue the case, or let it go unloved? Who preserves and saves those good things that others don’t see?

Criticism and exaltation are two sides of one coin; one never exists without the implication of the other. I know it looks like I’ve been masturbating to my own despair for six weeks, but behind every word there is pride and joy. I loathe Doctor Who. I love Doctor Who. I crave its death. I wish for its life.

We’re at the precipice. Chibnall has had his hand firmly on the reins for the entire first half of Series 11, and the results have been less than inspiring – in a sense, it’s on its knees. I doubt even Joe Public is going to stand for a repeat of Tsuranga. The grace period is over, and the show needs to start properly delivering.

The one thing we cannot yet predict is how the new writers will fare, completely free of Chibnall co-credits, and conveniently that’s what we’re about to find out with Demons of the Punjab. This next stretch of episodes from fresh voices will be the life or death of S11, and if it’s not too bold, I’d say it’s imperative that they be better.

But it’s not a guarantee. Being better is easier said than done, especially when Chibnall is still the albatross looming over everything. To be better, the new episodes need to escape Series 11’s fundamentally shallow ethos; improve the characters, embrace their medium of storytelling, scale up their ambition. It’s a hill to climb, and I’m unconvinced any of these newbies are going to be able to make it on their first ever attempts at Doctor Who. And if things go south, I won’t just be disappointed – I’ll be pretty fucked off. If Chibnall can’t put out quality episodes on his own, he at least owes it to the show to make sure the other writers can pick up the slack; otherwise he’s sending new recruits out to die on their faces, and the series with them. That will be the threshold at which banal incompetence becomes banal evil.

So…no playing nice. No redemptive readings. No excuses, or hedges, or mealy-mouthed evasion. Let’s demand better, as we press on into darkness.

(There is a high chance that as you read this, you will already have watched Demons of the Punjab. Savour whatever dramatic irony this may have produced.)

CATEGORY: Writers’ Room

- Well, I may have said all that, but the categories are still going to be shorter this week because – for the very reasons I outlined – this is an episode it’s tough to truly give a fuck about.

- The structure of the script is exceedingly wonky. It pads itself out egregiously; that “7-minute break” before the Doctor assembled everyone felt like an eternity. Effectively the entire first half consists of stalling tactics before the plot can begin, and then the middle section – between the reveal of the Pting and the final battle with it – is a bloated nightmare.

- The free space is used to cram in character exposition; particularly irksome is Yaz’s rather inappropriate interrogation of Ryan on the subject of his mum’s death. This happens because it’s the point in the series where Chibnall wants us to know about this, not because it arises naturally from the story.

- The script contains some twists and turns which are ill-thought-through. The Pting spits out the Doctor’s Swiss Army Sonic unharmed save for a power drain, yet everyone continues to assume that it wants to eat the ship; the Doctor’s final revelation occurs not because she came across new evidence but because someone said the word “energy” within hearing distance of her.

- I will admit, I wasn’t thinking about the episode enough on first viewing to come to any conclusions about what the hospital was, so I imagine some people out there were impressed by the twist that it’s a spaceship even if that seems to come under a lot of flak from other critics.

- Eve being revealed to not have one fictional disease, but in fact another fictional disease, serves to keep us held just far enough away from this subplot that we don’t appreciate the stakes until it’s already blown its load.

- Speaking of the sonic, it drops out of the plot then returns at its allotted time by…randomly reactivating itself. “Clever sonic! Self-rebooting!”

- The Doctor’s monologue about antimatter is another case of an ambient idea taking the place of content – it sounds educational, but impressively manages to not educate anyone about anything. It’s just jargon. That’s far from the main problem, though – it’s wank that adds nothing to the story. Oh, for sure, I’ve nothing against the Doctor going off on one when encountering an amazing new spectacle or concept, but in this case it’s…a glowing tube that powers the spaceship. Not exactly a feast for the imagination.

- Ryan and Graham helping deliver that baby is one legitimately respectable decision in the episode; having them do something together makes them both work in the same way it briefly did during Rosa. And them taking on pseudo-midwife roles serves as the sweet-natured stretching of masculinity that the plotline is asking for, although it’s within fairly safe and blokey constraints.

- Comparatively, the attempt to connect the whole affair to Ryan’s absent father falls flat and even takes on some worrying resonances (see last section).

- Iconic lines from this episode include: “Mate, that is epic!” “Yeah, I fix the things pilots like my sister tend to wreck, and she looks down on me for it. And she always will.” “Like a posh version of my uniform camera!” “No, I would respectfully ask, don’t talk to me.” “Do you mind me asking? How did your mum die?” “Why am I even talking about this?” “I love it. Conceptually, and actually.”

- By the way, while the episode is patting itself on the back at the end with that funeral for Eve, you know who isn’t mentioned at all? (I must thank Broken Mirrors for bringing this to my attention.) Astos. The first and only other character to die! He doesn’t get a lick of acknowledgement in the final scenes despite how much importance is placed onto him early on. It’s just kind of lazy. And sad.

![doctor_who_2005.11x05.720p_hdtv_x264-fov.mkv_snapshot_18.22_[2018.11.10_17.26.39]](https://gigawho.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/doctor_who_2005-11x05-720p_hdtv_x264-fov-mkv_snapshot_18-22_2018-11-10_17-26-39.jpg?w=863)

CATEGORY: Visual Big Finish

- The buildup to the Pting’s appearance largely consists of VBF. As the Doctor and Astos flail about in front of some screens in one room, we get another stream of verbal narration. (“Whoa, that thing can really move! It’s heading from the portside to the starboard!” etc.)

- The side characters are firmly ensconced in tell-not-show land. Our chief source for knowing that Mabli doesn’t believe in herself is the fact she says she doesn’t believe in herself and then people repeatedly tell her to believe in herself. In the case of Eve and Dirkus it verges on comical. (“I know all about your responsibilities, Ronan!” “Says the man who never wants any of his own!” “She’s a control freak, even to her own little brother. The most decorated general in Keeba history. 907 days in continual flight, on residual energy, fighting the Ayonians, saving our species.” Shut up aaaaaargh)

- For all the fancy effects shots with the Pting, the closest we get to any action involving it is a scene in which it’s represented by a blanket.

![doctor_who_2005.11x05.720p_hdtv_x264-fov.mkv_snapshot_35.25_[2018.11.10_17.30.59]](https://gigawho.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/doctor_who_2005-11x05-720p_hdtv_x264-fov-mkv_snapshot_35-25_2018-11-10_17-30-59.jpg?w=863)

- The spaceship is pretty well realised by Doctor Who standards, opting hard for style over realism; particularly of note are the wall panels which just have geometric shapes printed on them in black lines. It doesn’t look remotely technological, but nonetheless, the coherence of the aesthetic sells the representation.

- The Pting is another Series 11 case of the tone failing to maximise on the content, a little like some of those comedic and weird scenes in episode 1. It looks funny, sure, and it acts in a kind of funny way, it wiggles its little arse. But – with the exception of that final insane moment where we see a close-up of it orgasming in bliss from having a bomb go off inside it – it’s shot in a fairly plain manner. What rings particularly weirdly is that this is a story about the orderly world of a hospital being invaded by a force of sheer chaos and instinct, yet it doesn’t much feel like the Pting is even out of place. And the episode is rarely quite sure whether or not it’s in on the joke of this stupid little creature, or if it demands we take it seriously.

- Alright, nitpick – the “sonic mine” is just a cheap excuse to have the characters get fucked up and sent to a hospital without any visible injury.

- As usual, the music is like background noise, although (and you might notice this more if you watch it on fast-forward) almost every single little shift in the action is immediately flagged up by the synthesisers going bwaaaaaaaaahhhhh. It’s redundant and applied without sophistication. The really unforgivable moment, however, is at the climax of that antimatter drive monologue when – no! God, no! please, no! – a few notes of Thirteen’s leitmotif kick in. Just in case you didn’t get that this awful scene is a Doctory thing, she is the Doctor, and she is wonderful.

CATEGORY: Nostalgia

- As we alluded to earlier, a couple elements of this episode feel like an attempt to get back into the RTD era’s pants; a cute-yet-horrible CGI monster and an alien pregnancy? All territory he charted.

- Also, it’s far from the first time Doctor Who has done Alien. Although in this case, the creepy android dude just ends up being totally irrelevant.

- To the episode’s credit, though, Doctor Who hasn’t done “delivering a baby while fighting an alien” before – though there is a lick of Torchwood Series 2 to it (you know which episode I mean).

- At least it seems light on Pertwee homages this week, with the exception of that blink-and-you-miss-it Classic Silurian pettily included among all those NuWho monsters.

![doctor_who_2005.11x05.720p_hdtv_x264-fov.mkv_snapshot_18.13_[2018.11.11_21.33.45]](https://gigawho.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/doctor_who_2005-11x05-720p_hdtv_x264-fov-mkv_snapshot_18-13_2018-11-11_21-33-45.jpg?w=490&h=245)

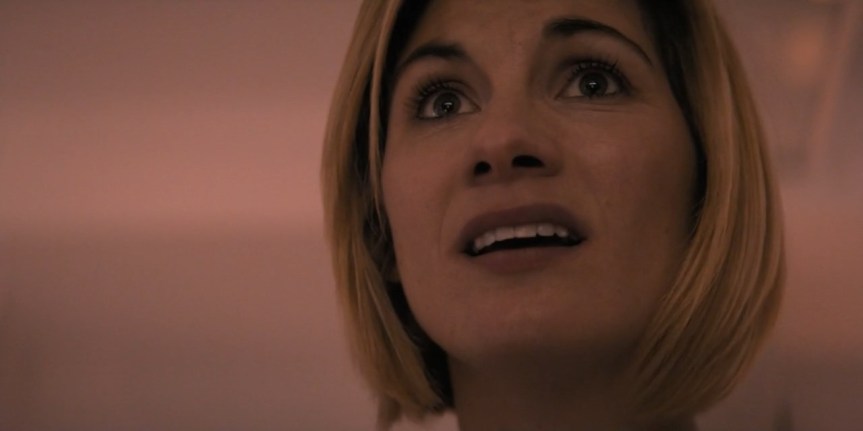

CATEGORY: Whittaker

- Something that perfectly illustrates the bind 13’s character is in: the scene early on where she starts to lose control, nearly sonics everyone to death and flips out at Astos. This may be the first time in five episodes we’ve seen her be a bit dangerous.

So how does it resolve?

DOCTOR: You’re right. Of course you’re right. I’m sorry. That mine hit me harder than I thought.

Oof. Yeah, go on, blame the sonic mine. It could never come about that the Doctor is just naturally an arsehole sometimes, no. We can’t have real, lasting friction between her and any of the others; she can’t make mischief, she can’t make serious mistakes, she can’t be volatile in any of the ways that make the character fun to watch from the get-go – she’s gotta be nice all the time ‘cos she’s a fucking PILLAR OF HOPE!- As a side note, I’m noticing that every time I’ve been genuinely charmed by 13 is a point when she’s been having fun at someone else’s expense. Wiping Ryan’s phone, claiming she’s Banksy, pulling faces at Robertson. I dearly wish it would happen more often. Whittaker’s performance seems like it’s ideally geared for irreverence and wisecracking, yet most of her material is just stuck on nice.

- Well, there’s “nice” mode, and then there’s “wonder” mode, which makes me wince. The entire antimatter monologue is an exercise in seeing how “in wonder” a human being can possibly sound while forcing out line after line of bullshit about positrons, and it’s like watching an actor in lead chains. Underwater. Whittaker is asked to carry the entire, crushing gravity of stopping the scene and plot dead in their tracks for the sake of this stupid speech, and the result is unholy.

- Eerily, at times the Doctor seems to be slipping back towards smug self-importance, but not in a self-aware RTD way – rather, it’s more like the show is smug about her and that bleeds into her dialogue. “I’d say it was more of a volume than a chapter. Just so you know,” seems like it takes place in a different show from episode 1’s “I’m just a traveller”, but then that episode contradicted itself too. Worse, of course, is the whole…

MABLI: A doctor of medicine?

DOCTOR: Well, medicine, science, engineering, candyfloss, Lego, philosophy, music, problems, people, hope. Mostly hope.

That line starts out okay then takes an obnoxious turn; it’s more self-aggrandising than anything we’ve heard from her thus far. I wouldn’t mind, but it’s not the version of the character we’re being sold in the rest of the show, and nobody seems to notice. The whole idea of shifting emphasis to the companions is seeming hollower and hollower as the Doctor becomes more prized by the narrative. The last shot of a character in Tsuranga is the Doctor in the prayer circle (the other members of the ring are glossed over), as if she’s the one who went on a big emotional arc here rather than anyone else. A strange echo of Rosa‘s bus scene with all those Doctor reaction shots. The show is conflicted about how much of a main character she is.

The last frame with a character in it.

![doctor_who_2005.11x05.720p_hdtv_x264-fov.mkv_snapshot_05.19_[2018.11.10_17.24.29]](https://gigawho.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/doctor_who_2005-11x05-720p_hdtv_x264-fov-mkv_snapshot_05-19_2018-11-10_17-24-29.jpg?w=863)

CATEGORY: Faux-woke

- It has the decency to be set in the future this time, unlike The Ghost Monument, but Yoss is yet another human-identical alien with a totally different biology. Needless to say, with the promo photos of him having leaked months ago, I was expecting something a bit more ambitious this whole time and it was rather a letdown. After all, if Jack can get pregnant…

- No, actually, this is seriously worth considering. You only have to Google image search “pregnant man” to see how unheard of and alien a concept it actually is, i.e. not very. If Doctor Who goes halfway across the fucking universe and to the 67th century and this is the most shocking thing it can come across – as an instance of a deliberately weird non-human species, no less – that doesn’t exactly suggest it’s able or willing to break some wild new boundaries with gender, despite posturing at exactly that. Considering right-wing bullshit merchants in the British media are angry about it anyway, despite the subplot not containing the merest hint of transhumanism or transgender people, one wonders what the point was of copping out so hard.

- Speaking of the pregnancy plot, is anyone surprised that Yoss’ anxiety about his unfitness for parenthood culminated in the “happy ending” of him deciding to go for it? Not without, it must be noted, encouragement from Ryan, clearly connected to his own parental abandonment…so, if I’m keeping up, giving up your newborn for adoption because you don’t feel you can successfully care for it is the same as walking out on your family? (I suspect these troublesome connections only arise because Chibnall lumped together the story elements on the basis of them all involving dads, damn the specifics.)

There’s the other strand of this, which is that Yoss suggests earlier that these “dark times” aren’t worth raising a child in, but ultimately changes his mind because of all the hope and love and stuff. Since those dark times are a non-veiled metaphor for our dark times, what we’re left with is a slice of brazen natalism – worse, reproductive futurism. Babies = good. Reproduce more. Climate? What climate? (And you’d better not even fucking think of aborting.)

But you don’t have to care about any of that to agree that it’s a teeny bit fucked up to devalue adoption as some tragic dereliction of duty. - Tsuranga reiterates the message of Rosa in a new shape:

- The future is just as awful as the present.

- It’s okay though because it all “turns out alright in the end” (direct quote from the Doctor in Tsuranga). Rosa got her asteroid, and stuff. Not much consolation to those people presumably being crushed and slaughtered right at that second – the only source of hope the Doctor has to offer is teleology; there’s nothing to be done right now but at least something good will happen in the future! (Even if you don’t live to see it.)

- As a final note, I hope J.K. Rowling doesn’t return to write another script for Chibnall, because I could really have done without all the hamfisted Corbyn metaphors. I mean, making him pregnant with Brexit? Seriously? And what was with Mabli constantly misgendering the Doctor behind her back? Very random and added nothing in my opinion.

Fittingly, as a result of writing this post this late, Demons of the Punjab is the first episode of Series 11 that I didn’t watch live. Feels like a watershed moment. I’m about to go watch it when I post this and get done cleaning it up.

Last chance, Chibshow.

“Oh, for sure, I’ve nothing against the Doctor going off on one when encountering an amazing new spectacle or concept, but in this case it’s…a glowing tube that powers the spaceship. Not exactly a feast for the imagination.”

A throwaway set which feels way more TARDIS interiory than the actual TARDIS interior.

LikeLiked by 1 person